So, even though I am technically cleared to take the driver’s test whenever now, due to some complicated boring stuff you don’t want to hear about, it might be a while before I do. In the meantime, I’m going to write a review, since I haven’t done that in a while.

Ghost World is a movie I can’t seem to shake. When I saw it for the first time, a little over three years ago, I was eighteen—the same age as the protagonists, Enid and Rebecca. Apart from age, I had apparently little in common with them. I was in college, which both girls in the film steadfastly refuse to attend. I was feeling unusually confident about the future at the time, whereas the girls are deeply uncertain. I was, and am, very bad at being mean; I would still much rather lie than hurt anyone’s feelings. Enid and Rebecca are experts at being mean; it is their primary hobby, the activity around which their friendship revolves.

Strange, then, that the film had such an impact on me. I found myself identifying with Enid and Rebecca to an extent I had never identified with characters in a movie before. (Who knows what that says about me.) Ghost World lingered in my thoughts for weeks, unwilling to be forgotten. My memory of the film was so powerful that, three years later, when putting together this blog, I placed the movie at #4 on my list of all-time favorites.

Last week I finally watched Ghost World for the second time. I was afraid that the movie might not be as good as I remembered—that perhaps, when I first saw it, I had simply been at a particularly receptive age. Maybe Ghost World only spoke to eighteen-year-olds. Maybe I would find it incredibly juvenile now that I was a whole FOUR YEARS into legal adulthood.

Having watched the film three times now, I suspect that Ghost World is not the kind of movie you outgrow. I don’t mean it has universal appeal; on the contrary, the movie is decidedly not for everyone! But if this movie is for you, it’s probably a lifelong relationship. You will return to it again and again, at various stages of life, and find that your perspective on the story has changed, but that the story itself is no less involving.

Here’s the story in vaguest possible terms: Enid and Rebecca, best friends who don’t fit in with anyone else, graduate high school. They have a sort-of-plan to get jobs and rent an apartment together, which Becky begins to take sort-of-seriously, much to Enid’s alarm. Meanwhile Enid, who seems content bumming around making fun of people, develops a significant relationship with Seymour, a socially inept collector of old blues and jazz records, whom she meets through a sequence of events I won’t spoil. This new friendship threatens to drive a wedge into the already widening rift between Enid and the more responsible Rebecca.

Here’s the story in vaguest possible terms: Enid and Rebecca, best friends who don’t fit in with anyone else, graduate high school. They have a sort-of-plan to get jobs and rent an apartment together, which Becky begins to take sort-of-seriously, much to Enid’s alarm. Meanwhile Enid, who seems content bumming around making fun of people, develops a significant relationship with Seymour, a socially inept collector of old blues and jazz records, whom she meets through a sequence of events I won’t spoil. This new friendship threatens to drive a wedge into the already widening rift between Enid and the more responsible Rebecca.

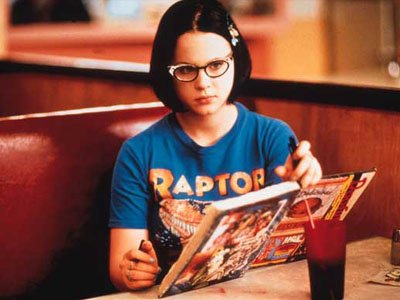

Forget all that. This movie is really about Enid, and she is one of the more complex and fascinating characters ever brought to life on screen. Enid’s problem, a not uncommon one in teenagers, is that her intellectual growth has dangerously outpaced her maturation in all other respects. She has a kind of X-ray vision for society’s BS, but has no idea how to channel this perceptiveness into anything constructive. Mostly she uses her intelligence to stave off boredom: she devises cruel pranks, fills her sketchbook with elaborate fantasies about the people sitting across from her at the diner, and amuses herself with caustic criticism of all things shallow and hypocritical.

It’s a risky move to put a character like Enid at the center of a movie. She’s not a person everyone can relate to, and if you can’t relate to her, her myriad flaws are hard to swallow. She isn’t always nice, to put it mildly. She does a lot of dumb things. She’s selfish, naive, and short-sighted. Thora Birch, whose performance is one of the movie’s most important assets, does something fairly miraculous with the character, and makes her likeable anyway. She accomplishes this feat not by toning down Enid’s abrasiveness in a cheap bid for sympathy, but by giving the character’s admirable qualities equal weight. As her relationship with Seymour develops, the movie suggests that Enid might, in fact, possess greater reserves of compassion than her quieter friend Becky, who dismisses Seymour as a loser out of hand. Enid, however, immediately responds to Seymour’s honesty and enthusiasm, and is moved by his loneliness. Elsewhere in the film, Enid’s insight, humor, and genuine affection for fellow misfits make her a character I find easy to root for in spite of her faults.

The other key to the success of Birch’s performance is how believably she cracks. As the film’s bleak latter half strips away the last vestiges of comfort from Enid’s life, it is both riveting and heartbreaking to watch her underlying fear and loneliness come to the surface. Birch’s performance takes on a sad, desperate quality. She becomes the character so thoroughly that she doesn’t have to say anything, and you know exactly what she’s thinking.

Ghost World is based on a comic book by Daniel Clowes. The script, which was written by Daniel Clowes himself in collaboration with Terry Zwigoff, the director of the film, is what I believe every adaptation should be. (It was also the first adaptation of a graphic novel to be nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay by the Academy; sadly, it did not win.) The movie differs from the book in a lot of ways—Seymour, one of the film’s most prominent characters, does not even exist in the comic—but the spirit is totally intact. I don’t see why an adaptation must be labeled “unfaithful” if it is anything less than a scene by scene reconstruction of the source material. It’s a movie! Movies and books are totally different things! A much more serious problem plaguing film adaptations is the obfuscation of the author’s original intent—and the best way to avoid this problem is to get the author involved. Not only did Daniel Clowes co-write the screenplay, he was also present on set during the entire shooting process, something totally unprecedented in Hollywood. As a result, the film and the comic feel like true companion pieces, complementary riffs on the same theme.

Clowes and Zwigoff labored over the screenplay together for more than a year, and their effort shows. The script successfully evokes the aimlessness of Enid’s life without actually being aimless, a tricky balancing act. Every scene accomplishes something, even when very little appears to be happening, and the film flows effortlessly from wacky comedy to dark drama. The dialogue is uncannily realistic, clever without once slipping into showiness. This is one of few movies with a sense for how teenagers actually talk—and maybe the only movie with a sense for how vinyl record enthusiasts talk.

Such a strong script still could have easily fallen flat with the wrong actors, and it might very well have, had Zwigoff been a less stubborn director. He refused to have the girls portrayed by 25-year-olds. (Scarlett Johansson was, in fact, only sixteen—two years younger than her character—when she played Becky.) He resisted ridiculous attempts to cast actors as varied as Harrison Ford and Freddie Prinze Jr. in the part of Seymour. The ensemble he finally put together is probably one of the most perfect ever. Everyone in Ghost World, whether they appear in one scene or nearly every scene, is brimming with personality. Take a video store clerk, who appears in one shot and has one line (“May I help you find a particular Masterpiece Movie?”) and still manages to make an impression. In addition to the three lead actors’ excellent performances, Ghost World has more memorable side characters than most movies have characters.

It is difficult to write about Ghost World without any mention of the ending, which is one of the film’s many iconic scenes and often debated. I won’t give the ending away, but I will say the movie neither condemns Enid, nor does it let her off the hook for her mistakes. It’s an ending written by people who care about the character a lot, but know that her problems cannot realistically be solved overnight. The final shots strike an emotional chord of exquisite, dreamlike melancholy. I can honestly say that no other movie has made me feel what the ending of Ghost World makes me feel.

I think Ghost World might be the funniest, saddest, and truest of all movies about growing up as an outsider. There really is no other movie quite like it. The enormous care with which the film was crafted is apparent in every frame. Did I mention it’s funny? That’s the one aspect of the movie I have probably neglected. For more than an hour of its running time, Ghost World is essentially a comedy, and it’s a really good one, the humor arising organically from the characters. But what elevates the film to classic status, for me, is its willingness to steer into turbulent emotional territory, and then its refusal to provide easy answers. The movie doesn’t side with Enid or Rebecca; it simply takes a good hard look at the compromises we are forced to make to become a part of society, and then asks us to reflect on those compromises. And that’s why I believe that, unlike a lot of teen movies, this isn’t one you outgrow: If you’re the type of person who reflects on such things now, you’ll probably be pondering the same questions years down the line. And when you find yourself wondering if your past decisions to conform, or to not conform, were the right ones, Enid will be there, wondering and floundering for answers right along with you.

Never saw this movie, but now I think I have to.

I can’t guarantee you’ll like it, but if nothing else it might provide some insight into my weird brain.